Some time back I finished reading what will be the lengthiest book I will have ever read. It’s The Mahabharata. The particular translation I picked is of little significance considering the broad outlook with which I devoured the book. Here I share some of my thoughts that I happened to make notes of as I read along. Invariably most of the comments may have an undertone of criticism. In Indian culture, The Mahabharata is popularly considered as a source of teaching a great many virtues. Perhaps diving into the book with such high expectations led me to ponder on the oddities that I mention below. One broad theme of virtue that I did find in the entire saga is that of Justness. Translated as Dharma (which also means duty), the tale teaches one to be just even in the most pressing circumstances. It has even been suggested that perhaps Mahabharata was a pioneer in introducing the concept of Just War i.e., adhering to criteria such as just cause, just means, proportionality, fair treatment of captives.

I’m tempted to comment on the historicity of the epic but that would lead me into a digression from my main objective here. Before I lay down my comments I present an oversimplified summary of the entire story.

Synopsis of Mahabharata

The entire epic is about a dynastic feud between two rival brethren of princes in the Kuru Kingdom. Dhritarashtra is a blind king who rules the Kuru Kingdom. He has a 100 sons called as Kauravas with the eldest of them being Duryodhana. They are the antagonists of the story. Dhritarashtra’s younger brother, Pandu (who briefly reigns before retiring to the woods), has 5 sons called as Pandavas. They are the protagonists of the story. They are (in the order of their birth) Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva. The last two are twins. Yudhishthira, the eldest of Pandavas is elder than Duryodhana, the eldest of Kauravas. When Dhritarashtra expresses his intent to step down, both of Kauravas and Pandavas claim the throne. The Kauravas then commit to a series of misdeeds ultimately forcing the Pandavas into a 13-year exile into the forest. Most notably, there’s an infamous game of dice played by Kauravas and Pandavas where the former cheat and win over the latter with the help of their cunning uncle Shakuni. Pandavas dutifully serve their 13-year exile along with their polyandrous wife Draupadi and return to stake their claim on the throne. Kauravas refuse to budge and this culminates in an epic 18-day battle between the two at Kurukshetra. Krishna (who is no less than a Supreme God in the Hindu Pantheon) sides with the virtuous Pandavas and Pandavas ultimately win the battle. All the Kauravas are slain by the end along with a lot of collateral damage to the Pandavas and for a brief period, the Pandavas rule their kingdom before which they ascend to heaven and Kali Yuga (the age of quarrel and strife) commences on Earth.

Observations/Comments

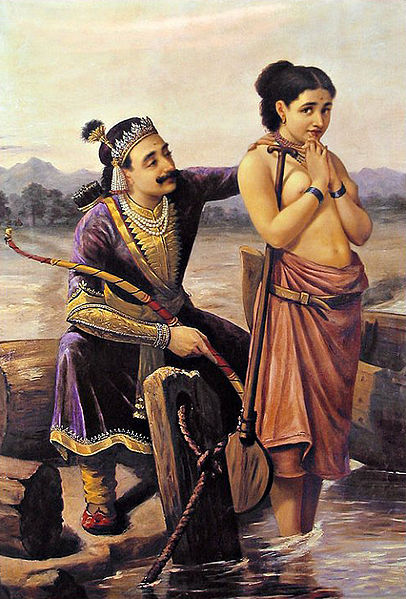

- Throughout the book, and especially in the beginning, there’s the theme of a lot of lust-filled Kings and men of Nobility. So much so that in one instance, Bhishma, the son of King Shantanu takes a vow of celibacy for life in order to let his father fulfil his desire to mate with Satyavati. The name Bhishma is today synonymous with stubbornness (in a positive way).

- Vyasa is supposedly the author of Mahabharata. He also happens to be the first son of Satyavati. He is considered a great Sage. Satyavati requests Vyasa to have sex with her widowed daughters-in-law Ambika and Ambalika – both of whom dislike sleeping with him. Ambika finds him revolting and closes her eyes while he lays with her (and hence gives birth to the blind son Dhritarashtra) and Ambalika turns pale upon seeing him in the bedroom (and hence gives birth to the pale son Pandu). He is actually summoned to have sex with them yet again but this time the widows send a poor maid under disguise instead (who gives birth to Vidura, a wise one, who later becomes the Prime Minister).

- Kunti, the wife of Pandu is unable to bear children (most likely on account of the pale Pandu’s infertility). She then uses a boon in order to give birth to the three eldest Pandavas Yudhisthara, Bhima and Arjuna – one each from the three Gods Dharma, Vayu and Indra respectively. She shares this boon with Pandu’s younger Queen Madri who bears Nakula and Sahadeva thanks to the Ashwinis (twin Gods). It is unclear whether these are supposed to be interpreted as virgin births or if there was sex involved.

- There are numerous other examples of lust and sex in the story but interestingly in every instance, the sex is meant for procreation and not for recreation. That is, the sex is portrayed as a need of the hour in order to inherit strong progeny who could then go on to rule the Kingdom. Thus its portrayed as if having sex is the duty of men. This is not in sync with the lustful motives with which the sex begins in most cases.

- In what was the most interesting episode to me, Arjuna, the most valorous warriors out of the Pandavas visits Krishna’s Kingdom and falls in love with Subhadra, Krishna’s sister. He then goes on to ask her hand to Krishna. Now Krishna could have either expressed his approval or disapproval. But instead, he goes on to advise Arjuna to elope with his sister rather than marrying her in peace. He justifies this course of action by emphasising how a warrior is supposed to show his strength and character by eloping and dragging away the woman he likes instead of courteously asking out for her hand to the elders. The entire episode is quite comical which leads to an unwarranted scuttle and eventually ends in an amicable matrimonial alliance anyway.

- It would be unfair to judge the story from the modern prism of gender equality considering it hasn’t even been a 100 years since most of humanity adopted the principle. Nevertheless, it has to be duly noted that the theme of women being restricted to proper maintenance of the household and completely devoted to their husbands is a recurring theme in the book. Draupadi is portrayed as an ideal example of the dutiful wife in this Epic. Gandhari, the wife of Dhritarashtra is also held in similar reverence since she blindfolds herself on account of her husband being blind.

- Perhaps no other episode of Mahabharata is more famous than that of the game of dice played between Kauravas and Pandavas. In modern times this episode is quoted as an example to support the immorality of gambling. Yudhishthira is apparently addicted to gambling. He is invited to play the game by Kauravas. He accepts the invitation and begins to lose each round of the game thanks to the cunning Uncle Shakuni who’s the one throwing the dice. Yudhishthira loses his possessions, his wealth, his empire, his wife, his brothers and finally himself all in succession. It’s ridiculous to even think that a person could put themselves at stake in a match of gambling. But interestingly after some drama, everything is restored to him and he is invited to play once again. And for the second time Yudhishthira plays the game only to lose again and this time he along with his wife and brothers are exiled for 13 years. The emphasis in this episode is laid on how Yudhisthara was compelled to play on account of being invited by his elder, namely Dhritarashtra, and not because of his own will (and his addiction to the game). Also, for what its worth I didn’t see how Kauravas “cheated” Pandavas in this match. It’s a simple game of throwing two dice with a 1/36 probability of winning in each turn.

- Revenge is glorified repeatedly in the stories. Not only is it glorified but it’s even portrayed as the duty of Kshatriyas (the warrior class) to seek revenge. Today it is generally agreed that revenge breeds more violence and hatred and thus forgiveness is instead considered the nobler virtue.

- If the book were to be certified by censor boards it ought to get an X-rating. I say this on the account of brutal violence portrayed in the book. I would most certainly not recommend the book to anyone below the age of 13. Bhima, who is a mountain-like character in the Epic is voracious and is often compared with Rakshasas (demons), and rightly so. I recoiled on the part where he splits the thighs of Duryodhana at the end of the book. There are other parts where he tears apart the limbs of his enemies, crushes their heads and drinks their blood. Such gore is unsuited for a book that is purportedly also a devotional book to most Hindus.

- DONATE to Brahmins. This is a recurring theme in the book and for unsurprising reasons. The role of Brahmins in the book and in the history of India in general warrants a separate sociological account in its own right but one would not miss this repeated emphasis laid on the need for everyone to keep donating to Brahmins. Being the priestly class they are portrayed as the ones who live on the alms and donations of Kshatriyas and Vaisyas. Yet there is no hint of humility or servile attitude on the priests’ part. Moreover, there’s a very deep conflict of interest at play here since Brahmins were the ones who significantly shaped the form of the Epic as we know it today.

- It’s quite surprising to see the God Shiva make an appearance in the book! This must be undoubtedly inserted in the later revisions of the epic. According to The Mahabharata itself, the original version consisted of only about 24,000 verses which were later inflated to 100,000 verses. Unfortunately, Shiva, the Lord of destruction, makes his appearance only briefly. It would have been a very interesting addition to the story had a conversation between the two Gods, Krishna and Shiva, been amalgamated into it.

- Many characters in the book are exaggerated ornately. And many are even considered God-like with almost superhuman qualities like extreme austerity and unrelenting adherence to principles of Dharma and so on. But Krishna is the only ACTUAL God that is present in the story (apart from the brief cameo of Shiva mentioned above). And it’s interesting to note that Krishna is not modest when people praise him. Some of his speeches are what I would count as humblebrag according to modern standards.

- Krishna, as mentioned before, is a major God in Hinduism. And he has his own dedicated literature which is no less in its epic proportions compared to Mahabharata. He is also considered as a mischievous God. And a lot of his mischief can also be seen in the Mahabharata as well. However, it’s an oddity to juxtapose Krishna’s advises with the higher ideals that the other characters try to bring out. For instance, he repeatedly advises bending of rules in War. Yudhishthira who has an impeccable record of being truthful and never ever lying is compelled to lie about Ashwathama’s death (son of the Kuru war chief Drona) on the advice of Krishna. This lie emotionally shatters Drona eventually leading to his death which then gives an edge to Pandavas in the battle. Similarly, Krishna manipulates Duryodhana at the end to cover his thighs when he goes to see his mother. Because of this, his thighs are left out of his mother’s boon (kind of like Achilles heel) and remain his weak point. In the ultimate duel between Bhima and Duryodhana, Krishna once again cheats by telling Bhima about Duryodhana’s weak point – his thighs – and enables Bhima’s victory. There are several other examples of Krishna bending the rules in such a manner. It just doesn’t fit in with the broader theme of idealism that is presented in the epic elsewhere.

- After the days long battle had been won with a lot of collateral damage Yudhishthira is supposed to sit on the throne and rule. That’s what he fought the battle for and that’s what so many soldiers had given up their lives for. They believed in him and his cause. And yet soon after the battle, Yudhishthira repents and quite peculiarly asks what a king is and what are his duties? Maybe the point is that the experience of war has changed him completely – but this is not borne out by other facts. Moreover, these were the questions that he should have asked before embarking upon the battle in the first place.

- Krishna teaches a lot to both Kauravas and Pandavas. Mostly it’s the Pandavas who are receptive to his teaching and perhaps worthy of understanding his teachings. The Bhagavadgita, which is Hindu equivalent of Bible, is also part of Mahabharata and constitutes one such long discourse by Krishna. Its where Arjuna begins to question his duty as a warrior right in the middle of the battlefield. What sense does it make to slay his own brothers and family? What peace will he be able to restore after this battle? And so on. Krishna convinces him that his duty as a warrior is to fight and win the battle. In the end, there’s also a spiritual discourse on letting go of material attachments and how everything is transitory etc. And yet, soon after Krishna dies, Arjuna (who supposedly learned everything that Krishna taught him) begins to cry uncontrollably. This shows he is still attached to the God, something he should have let go of by then.

- Atheists are treated on par with untouchables! Untouchability is a practice that was quite unique to Indian culture in its form and scale. Untouchables are considered a class that is completely out of the 4 traditionally recognised classes in Varna system. That is, they are considered subhuman. In Mahabharata, atheists are also equated with untouchables. Not that I could care any less about their judgement of atheists but how insulting!

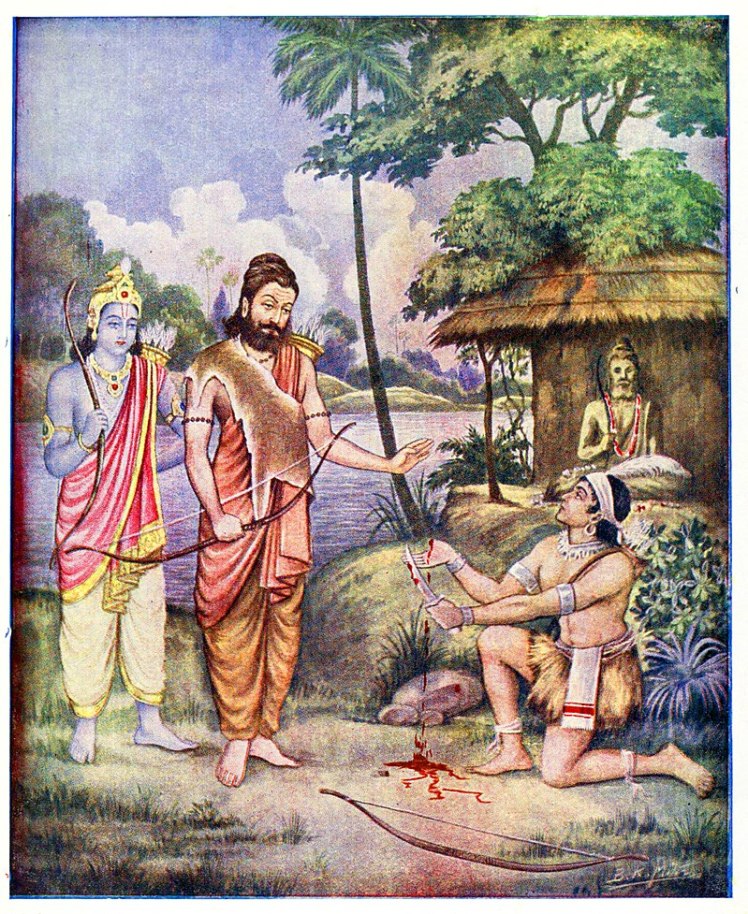

- Early in the story, there’s an episode where Drona (Guru of both Kauravas and Pandavas) hears of a lower caste tribesman Eklavya being a great warrior – perhaps an equal of Arjuna at Archery. Eklavya seeks to become Drona’s disciple. Drona refuses on account of him being from an inferior caste. When Eklavya insists that Drona teach him, and Drona realises that Eklavya is able to teach himself and become as good as Arjuna, Drona asks him to give him his thumb as Gurudakshina. Eklavya chops off his thumb promptly in obedience to his master and thus disables himself from becoming the great warrior that he could have been. This was just a mean act by Drona – the point of which is unclear to me.

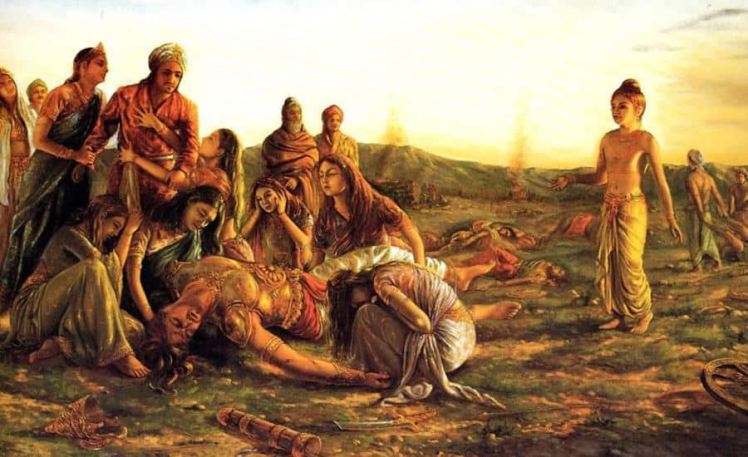

- There’s a good enough prose dedicated to the tragedy of war and the loss it brings to all sections of people who have a stake in it. And yet there is a noticeable neglect of lamenting for the death of ordinary soldiers and death is emphasised only when someone great falls in the battlefield. Multitudes of soldiers (most commonly mentioned in thousands – of course exaggerated) dying on the battlefield like flies in a storm are not at all mourned for.

In conclusion, the story is of epic proportions with hugely exaggerated and idealised characters. It’s a story where Gods walk on Earth along with great men. The story has been modified tremendously over the centuries amalgamating new cultural tropes as it evolved. Most Indians are familiar with bits and pieces of the story, if not in its entirety, and for any Indian History enthusiast, reading the story is a must. And perhaps the inconsistencies in the epic along with the mistakes that even great men commit serves only as a reminder about the infallibility of men.